A row of huge oak trees lines the walkway between the plantation home and the Mississippi River at Oak Alley plantation. Pam LeBlanc photo

When I visited Oak Alley Plantation a decade ago, tour guides in antebellum gowns led me through the Greek Revival style mansion, showing off fine furnishings but making only passing mention of the slaves who toiled there.

Today, though, visitors get a more complete picture of life at the sugarcane plantation best known for a walkway lined with gracefully bending oak trees. They can still explore the column-lined home where wealthy planter Jacques Roman and his family once lived, but they can also learn about the more than 200 enslaved men, women and children who supported the family over the years.

An exhibit that opened in 2012 includes six re-constructed slave quarters buildings, set close to their original location near the mansion. Inside those structures visitors can read about the daily lives of field and house slaves like Pognon, a seamstress; Anna, who made lye soap; Emelia, who dug ditches, repaired roads and maintained the levee; and Antoine, who grafted the first papershell pecan tree, opening the door for commercial production in the area.

One cabin represents a rustic (and unsanitary) “hospital” for slaves who had been injured or were sick; another houses a collection of artifacts, including reproductions of shackles and neck irons used to restrain slaves that were being punished. The names of the slaves who lived at Oak Alley are etched across the wall of another.

“It’s a place that is so beautiful but has such a dark history,” Hillary Loeber, director of marketing at Oak Alley Plantation, says of the plantation.

The slave exhibit

This reproduction of the slave quarters at Oak Alley Plantation gives insight into how more than 200 enslaved men, women and children lived. Pam LeBlanc photo

The slave exhibit was years in the making. The plantation’s curator, collections manager and department of research and interpretation worked together, digging into archives and sifting through records from all over Louisiana and beyond. They used records of slave sales, baptisms and marriages, census data and, for cross referencing, genealogy sites like Ancestry, to piece together individual stories about the men, women and children enslaved on the property. Because many of the slaves were referred to by different names on different documents, the work was tedious.

“It’s a major feat to go in and cross reference documents, especially since different cultures are involved,” Loeber says. “People had a different way of writing and speaking, and names changed over the years. To trace people back from now to then, especially in the slave community, it’s quite difficult.”

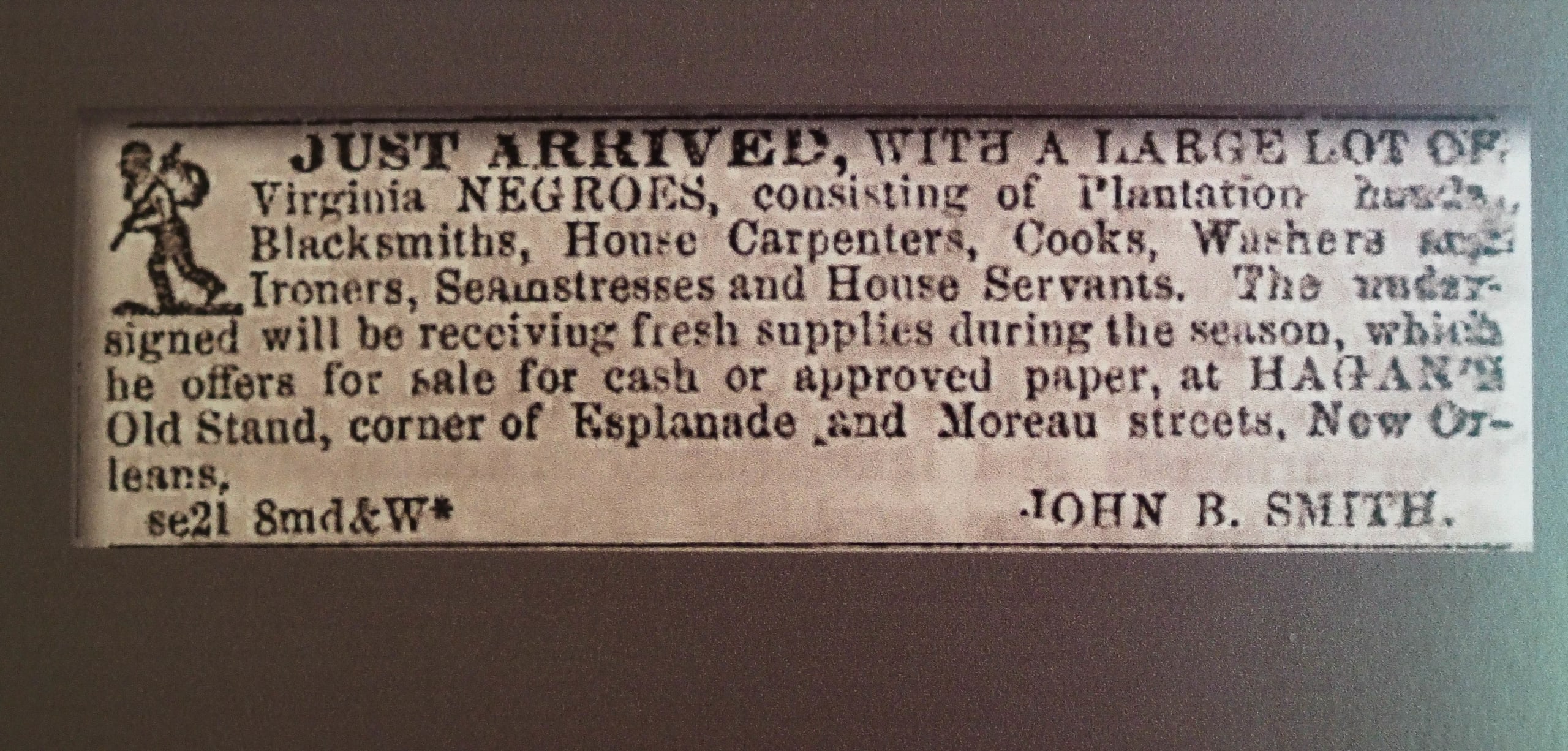

A reproduction of a newspaper advertisement at Oak Alley Plantation. Pam LeBlanc photo

Much of information the researchers uncovered is available to the public via the plantation website’s slave database.

RELATED: Seminole Canyon’s world class rock art is a lens to history

The slave exhibit at Oak Alley Plantation provides a good balance to a tour of the Big House, a 180-year-old mansion where Jacques and Celina Roman raised their family in relative luxury.

“We went away from the previous tour, with guides in antebellum dresses and folklore passed down by word of mouth, to a tour focused on historical facts,” says Janell Napier, who led a small group of visitors through the Big House during my most recent visit in May.

Touring the Big House

Visitors to Oak Alley plantation can tour the main home, the grounds, and replicas of cabins where slaves once lived. Pam LeBlanc photo

Walking through the home, you’ll see the dining room, where a slave pulled a rope to move the “shoo fly fan” that hangs over the table, the parlor, and the bedrooms where the family lived.

Jacque Roman died at age 48 in 1848, and his wife Celina took over operations of the plantation, but it fell into financial hardship and was sold in 1866.

Eventually, the Stewart family purchased it in 1925. Josephine Stewart lived there until 1972, and created the non-profit Oak Alley Foundation, which maintains 63 acres of the original 1,200-acre property today. The grounds include lush gardens, a gift shop, a café, and a bar where visitors can order a mint julep. There’s also an artifact room that reinforces the paradox that the plantation was a comfortable residence for the wealthy owners and a place of pain and abuse for the slaves.

The famous oaks

The 28 oak trees that line the walkway leading from the Mississippi River to the front of the home remain a highlight, but research has changed the staff’s understanding of how they got there. The trees, between 200 and 250 years old, form a tunnel of green, and a walk beneath their canopy will whisk you back to a different era.

RELATED: Discover history and simple pleasures in Baffin Bay

“For the longest time, the story was the trees were planted 300 years ago by an unknown French settler,” Loeber says. “Since then, we learned by cross referencing documents and land grants that the trees could not have been here at that time. A carriage road went through alley then, so it’s more likely the trees were transplanted here later using slave labor to create an alley.”

There’s no official documentation on who did it and when it happened, but the original carriage road that cut across what is now the row of trees was closed in 1807, and researchers believe the trees were planted about 80 feet apart sometime between 1820 and 1836. It’s just one example, Loeber says, of how what we know about the plantation’s history continues to evolve as researchers uncover new information.

“The visitor experience is important to us and sharing correct information is important to us,” she says. “Our mission states for us to preserve, research and educate the public, and slavery was a part of Oak Alley’s history at the time it was built, so it’s our responsibility to research that and educate on it. But it’s important to us not to speculate or generalize. We’re not here to give the full history of slavery because it is so complex.”

Besides the guided home tour, guests can do a self-paced tour on their own. Site interpreters mingle with visitors to answer questions and spur conversations. A new guidebook published in May and available at the property provides an overview of that history from the early 1800s to the creation of the foundation in 1969.

“When visitors come, it’s not just a house tour, because a house is not a plantation,” Loeber says. “We want them to understand all aspects of the history, and slavery was a very integral part of that.”

If You Go

Getting there:

Oak Alley Plantation is more than a seven-hour drive from Austin. Located at 3645 Highway 18 in Vacherie, it’s about an hour’s drive south of Baton Rouge. Admission to the grounds is $25 for adults or $10 for ages 13 to 18, with a $2 additional charge for a home tour starting in August. Beginning in August, visitors may book tickets for specific times in advance online. The plantation is open from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. daily (closed major holidays). For more information go to www.oakalleyplantation.com.

Stay:

Overnight lodging is available in one- and two-bedroom cottages on the plantation grounds. Rates range from $150-$325 per night, and breakfast is included.

Do:

Other historic plantations, including Laura Plantation and Houmas House, are located nearby. Visitors can also take airboat tours, rent kayaks, or look for alligators with local tour providers, or sign up to take a Cajun cooking class in Vacherie with Spuddy’s.

Eat & Drink

The onsite restaurant at Oak Alley is open for breakfast and lunch, but not dinner. Pre-prepared meals (think gumbo, crawfish etouffee or red beans and rice) are available to reheat in your room. Better yet, head to New Orleans!

Pro tip:

Be prepared for heat, humidity and rain. Temperatures might only reach the upper 80s, but it will feel hotter. Carry an umbrella.