A matador is a celebrity of sorts in Spain. Photo courtesy Rick Steves

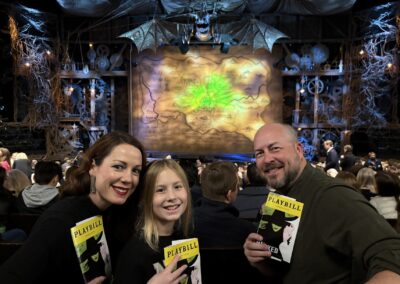

I used to date a matador.

That was years ago in Seville, when it was a quieter, less-touristed city, though still the bullfighting heartbeat of Spain, as it remains today. Back then, there were few animal activist naysayers, and though I was a vegetarian and loved animals, I still trembled to see my graceful paramour amid the swirling dust of the bullring, his bejeweled silk suit like a second skin, his dance with the bull like a surreal foreplay, a public display of affection just for me.

I won’t lie — he was drop dead sexy.

In those times, to gallivant with such a nimble nobleman in the centuries-old bodegas or cafes of Seville, to hold his arm as we took a paseo in the afternoon, was to be a celebrity as well. And being young and foolish, I relished the attention. Moorish and mysterious, the city spoke only Spanish then and people clung to ancient traditions, worked the same jobs as their fathers and rarely left the boundaries of Andalusia, Spain’s most southern, and — in my view — most truly Spanish province.

For him to date someone like me (a green-eyed, blonde-haired American) in this flamenco-intoned, somewhat unyielding and rather lugubrious world, was cheeky and rogue. Matadors weren’t internationally acclaimed, but in Spain, they were royalty — and a certain protocol was expected.

RELATED: Oyster safaris and mystery solving along Sweden’s coast

Becca Hensley has had a long-running love affair with Spain. Photo by Becca Hensley

An annual trip

So, of course, it didn’t work out. A year later I had a boyfriend from Hollywood, but my love affair with Spain lives on. I journey there annually, ever entranced, always enthralled. I go to soak up the vestiges of old world Spain that surge still like a subterranean river beneath the globalization that has become today’s Europe. I visit to seek out the lingering perfume of horse dung and cobblestones on medieval pathways, the nutty scent and taste of sherry from Jerez, served in a thimble-sized glasses by octogenarian bartenders who will surely never die, to be enwrapped in the aroma of orange blossoms in full bloom.

I come hungry for the cuisine, foamy and swank in Barcelona, rough-hewn, unpretentious and garlicky in Andalusia, urbane in Madrid and civilized and old school in Rioja and the Duero. I journey here to be refueled by that barely contained Spanish gusto for life, a lifeblood coursing through the veins of Spaniards from all parts of the country, despite the inherent differences from province to province, regardless of age or occupation.

Winemaking with friends

Each visit brings new discoveries. On a recent jaunt, I join a group of winemaking friends for a calcotada, a springtime rite of passage in Catalunya, a northern region that embraces the canny city of Barcelona. Celebrating the leek-like calcot, the usually informal fete involves a fiery barbecue grill, baskets of just harvested calcots, bowls of rich Romesco sauce, bottles of champagne-method-made Freixenet cava and a gusto for life.

Mesmerized, we gather around the grill, watching the mildly sulfurous, tubular-shaped vegetable cook until the exterior is charred, at which time the chef plops it atop one of the red, ceramic roof shingles common to the region — a makeshift plate that deeply roots us to the traditions of this place.

Whisking the blackened sheath away with our fingers, we grab the calcot by one end, messily dipping it into a bowl of Romesco (a tomato, garlic, hazelnut and almond sauce), then dangle it above our heads, mouths upturned and agape. With a flourish, we lower the length of the calcot down our gullets, in one continuous — and very suggestive — movement. To cheers and laughter, we emerge with Romesco smeared like red lipstick all over our faces to wash the last of it down with effervescent, clarifying tipples of cava before starting all over again.

Traditionally, the calcot serves as an appetizer with a meal of lamb, fresh salads, flowing Freixenet and flavorful oranges to follow. We indulge in all of it.

RELATED: A baker’s dozen of the best historic spas across the world

A fair in Seville draws flocks of tourists. Photo courtesy Rick Steves

A return to Seville

Still, it’s when I return to Andalusia’s Seville a few months later that I feel most alive — even without a matador in tow. I walk through meandering, cobble-stoned streets, medieval houses framing my steps and pass through thresholds that link neighborhoods. Beneath the shadow of the cathedral’s iconic tower, La Giralda, I conjure memories of Semana Santa, the Easter-time celebration where the statues of virgins are carried through the streets by pointy-hatted penitents.

And I muse over Feria, Spain’s biggest springtime party and horse festival, during which the whole city of Seville seems to close down. I remember walking amid the horses, overflowing plates of fried pulpo being passed around and the caseta — or booth — where wine could be drawn from a well with a wooden bucket. That still happens. But being here in summer, I head to a favorite bar in the Macarena, a storied barrio just outside the city’s original walls.

I pluck down on a stool at Bar Plata, a place that hasn’t changed since I lived here — maybe hasn’t altered for more than a century. The barman brings me a tiny glass of ruby-colored tinto and a tapa of garbanzos with espinaca. He looks familiar and we stare at one another doubtfully. “You like spinach?” he asks, running a hand through his grey hair. “Si, como no,” I say, sipping my wine. “I used to know an American girl who liked spinach,” he continues, looking at me quizzically. I wait. “She used to come here with a matador.” A pregnant silence, heavy in the air, makes him turn to fiddle with a gleaming espresso machine. When he does, I smile to myself.

“La vida es sueno,” I say.

And, he nods, as if captured in a dream.