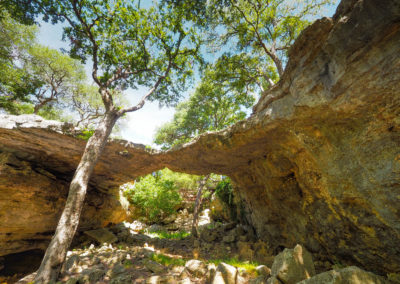

Andrea Tinning’s grandfather crashed in an airplane in these hills of North Macedonia in 1944. Photo courtesy Andrea Tinning

I sat in the backseat of a beekeeper’s car, speeding through a winding road in rural North Macedonia in the middle of the night.

Not a single friend or relative knew my whereabouts, and as I looked out the window at the dense forest that obstructed whatever view wasn’t already shrouded by pitch darkness, neither did I.

Filip, the beekeeper, said we were headed to a house that was “older than the United States of America” and had been in his family for generations, and quite possibly was where my grandfather took refuge almost 80 years ago. If I was right, I was about to see a relic from a story I’d heard about for years: my grandfather’s rescue from Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia in 1944, as well as the rescue of hundreds of other fallen airmen through a network of clandestine airfields that went undetected inside enemy territory.

Memorial Day significance

Memorial Day is special for me this year since my trip to the Balkans in September. I followed the footsteps my grandfather had outlined in his Military Aircraft Crash Report when he was declared Missing in Action during the summer of 1944. What happened between the time his plane crashed in the mountains of Yugoslavia and his return to base in Italy months later was a story he seldom spoke about with members of his own family – in part by choice, and partly because the details of his rescue were classified for decades.

A number of things prompted my obsession with Jack’s war story. Some may call it “intuition,” others “a spiritual quest” or even “a mild case of psychosis,” but I had a feeling that if I followed this thread, I’d find something worthwhile at the end. At the very least, I would understand myself and my family better.

“I’m no hero, all I did was walk home.”

My grandpa said those words to his children whenever they mentioned his military service. He joined the Army Air Corps in his early 20s, he said, because he didn’t want to have to march. He ended up hiking across mountains near Samokov, North Macedonia, from August until October, while local resistance movements caught in their own civil war worked together to plan his escape by aircraft. According to one of the military documents, villagers used torches to guide two C-47 planes to a makeshift landing strip in the middle of the night. It had rained; the plane got stuck in the mud. Over 150 villagers and 8 oxen helped drag it out.

These are the meticulous details he never shared, but they came to life for me when I put the coordinates into Google maps on my trip to Macedonia.

Help from the locals in North Macedonia

I met Filip in the small mountain town of Samokov, where a cafe serves as a local meeting point. I sat down and ordered a coffee and sausage, using the Google Translate app on my phone. The sun was setting when I realized I had booked a hotel in a town by the same name in Bulgaria. I looked around, and people seemed to notice me as day turned into night and the cafe became a bar.

I had nothing to lose, so I took a risk and typed into Google Translate: “My grandfather was rescued by people here when his plane crashed in 1944. Does anyone know this story?”

I handed it to the cafe owner as he took my plate. He looked at the phone, then at me. Then he took the phone and passed it around the people at the restaurant. He went outside. Suddenly the cafe came alive and everyone wanted to talk to me. Nobody in the cafe spoke English except Filip, who said his family once housed an American soldier who fell into the woods when his plane crashed into a mountain not too far from where we were standing.

Before I explained anything, he repeated to me details of the story I had collected through anecdotes and research – parts of which my own family didn’t know. Filip said his family rescued the soldier because an enemy base was located about 3 kilometers away, and if they didn’t help the man, he would be discovered by people who might kill him.

This oxygen tank was salvaged from a plane that crashed in North Macedonia. Photo courtesy Andrea Tinning

That’s how I found myself in the semi-basement of a house surrounded by woods in the middle of the night in North Macedonia. Filip had taken me to see the pieces of the plane his family had kept as scrap metal. He showed them to me: Four metal oxygen tanks from the wreckage of the B-24 from which my grandfather jumped.

Grandpa Jack

Andrea Tinning traveled to Macedonia to learn more about her grandfather, Jack Tinning. Photo courtesy Andrea Tinning

My Grandpa Jack died when I was very young; but I’ve learned about him through the memories of his children.

He would attribute heroism to the people who sacrificed their lives to get him home, starting with the pilot and co-pilot of the plane – his friends whose bodies were burned beyond recognition, according to statements made in the military report, and buried somewhere in the very woods I was standing.

There are certain things that you can learn or conceptualize, but can’t understand until you experience them. That’s what it was like touching that metal.

Read more: Science, history and culture on a Smithsonian Journeys cruise to Panama

I’ve heard through family lore that Jack’s peers nicknamed him “Grandpa;” presumably because he was the oldest in the crew. But looking at the crew reports, I learned he was not the oldest.

What I do know about Jack: As a teen, he loved the opera. He was a devout Catholic and did not have a girl waiting on him at home during the war. He valued his education, and would graduate college with a double major in engineering and physics – by accident– because of classes he elected to take.

I’m no Sherlock Holmes, but I think his friends were teasing him. It turned out to be a prudent assessment, as he would live to see the births of a dozen grandchildren in his lifetime.

What the trip to North Macedonia meant

It is hard to sum up exactly what this moment meant to me, realizing my entire existence may very well be the manifestation of a punchline my grandpa’s friends were willing to die for.

The jokes these young men made as they prepared for a war; the lives they left behind in order to rise to the challenge of their present moment; the lives they could have had if they weren’t asked to make the ultimate sacrifice during a global crisis they didn’t want to see unfold, and for that reason had to be participate in order to stop it – all became clear to me.

It was also hard not to see how not to see myself in Jack’s story: As someone who went through a global disaster in my early 20s that had its own demands, meet those demands as best I could, and become frustrated that my small part wasn’t enough to prevent others from having to pay the ultimate price.

At that moment, it came to life for me. I realized that heroes start as victims of circumstance – most of us can’t help the state of the world at large, but the choices we make in the face of those challenges are up to us.

I think good people are ones that do the right thing when they don’t have to. Heroes are the people who do it when it costs them.

After we looked at the wreckage, Filip showed me the room where he makes honey and rakija, a type of brandy native to the Balkans. We chatted about the continuity of what we were experiencing – how our ancestors may have been in the same room sipping the same drink – and what we could learn from them as we face the uncertainties of our own time.

Filip told me about a plant that grows in Macedonia called pirej. It’s hardy and in some places is considered invasive. It can be dried 100 years, replanted, and thrive.The poet Petre Andreevski compared it to the resilience of the Macedonian people – no matter the adversity, their spirit cannot be destroyed.

I think the same is true for courage.

This Memorial Day, I honor Donald Gilbert and Clyde Hayden, the young men who piloted and co-piloted the plane and kept it steady long enough for my grandfather to escape. I think in moments of crisis, I will always remember their sacrifice, and the courage of everyone who helped him in his walk home.