Jimmy Harvey rows as Steffen Saustrup holds down the bow at Crystal Rapids on the Grand Canyon. Pam LeBlanc photo

As I drift slowly toward Hermit Rapid, a frothy Mixmaster of turbulence at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, the roar of water drowns out every sound –– except, possibly, the silent scream inside my head.

My buddy Jimmy Harvey, who is at the oars, looks serious for a change. I double check the buckles on my lifejacket and helmet, and brace for the liquid wall we’re about to hit. Next to me, Steffen Saustrup helps hold down the bow.

Jimmy pulls on the long, spindly oars. The nose of our boat spins toward the freight train of standing waves, and suddenly we’re in the thick of it. We dip, then buck into a swell the size of a school bus. I’m positive, briefly, that our raft will fold in two like a taco, but it springs back to shape, just in time to ricochet through eight more waves, each one capable of flipping a raft.

It’s the first day of two weeks I’ll spend rafting through the Grand Canyon, and I can already tell I don’t want this adventure to end.

John Beard’s dream to raft the Grand Canyon

John Beard attempts to navigate Bedrock Rapid while rafting the Grand Canyon. He missed his line, went around the back side of a boulder field, temporarily lost a passenger and snapped two oars. Pam LeBlanc photo

John Beard, 57, first saw rafters navigating the frothy waters of Hermit Rapid when he was 32 years old leading a group of Texas A&M University students camping along the Colorado River at Grand Canyon National Park. He couldn’t take his eyes off the boats he watched pass through the roiling water. One day, he decided, he would do it himself.

“It looked exactly like a roller coaster,” he says of that long-ago memory. “Just a bunch of standing waves in a row going up and down and up and down.”

That year, he put his name on a waiting list for a permit to organize his own 21-day private rafting trip through the canyon. The National Park Service issued him number 3,750.

He waited years. In 2006, when the system changed from a waiting list to an annual weighted lottery, his number still hadn’t come up for the time frame he wanted. (He and his wife were busy competing in adventure races like Primal Quest and Eco-Challenge around the globe.) But finally, in 2018, Beard got word he could pick a date to go.

Beard chose a September 2021 departure –– after the monsoons and the worst of the heat had passed, but before the cold set in. (That was a good call. One rafter on a commercial trip died in 2021 after unusually intense monsoons caused a debris flood.)

Finally, 25 years after he first applied for a permit, he would get to run Hermit Rapid –– and more than 80 other big water rapids –– first hand, at the oars of a bright yellow, 18-foot rubber raft.

We had four 18-foot rubber rafts and several kayaks in our group. Pam LeBlanc photo

Planning a rafting trip through the Grand Canyon

The planning began. From selecting the right group of people to provisioning the trip, John and his wife Marcy, whom he’d met long after first applying for that permit, went to work.

“I always imagined it would be really good to be here with people in a moving town,” Beard said.

Because I knew several other folks on the trip, which was made up of adventure racers and endurance paddlers, I was invited to join the fun.

Sixteen folks would put in at Lee’s Ferry. After one week, four would get out at Phantom Ranch. I was one of four others who would hike down from the South Rim to take their spots for the remaining two weeks.

On a cool morning in late September, I waved goodbye to flush toilets and tap water, slung my 32-pound backpack over my shoulder, and began the 9-mile trek down the Bright Angel Trail to the Colorado River. Shortly after noon, I stuffed the contents of my backpack into dry bags, loaded it onto one of four rafts in our group, and pushed off.

We jumped right into the fray.

That first day, we blasted through four big rapids –– Horn Creek, Granite, Crystal and Hermit –– where I whooped and hollered as we alternately launched into the air and crashed into swirling holes of chilly water.

RELATED: Paddling the Devils River

That night, I skipped the tent and rolled out a tarp and my sleeping bag on a sandy beach. I wanted to gaze at the stars that popped out against the velvet of the night sky and think about how small I felt down here at the bottom of this vast canyon.

Then the wind kicked up, blasting sand into my face. A few hours later, raindrops began splatting against my nose. I scrambled to put up my tent in the dark.

More than just rafting the Grand Canyon

Jimmy Harvey jumps into a pool of water at Elves Chasm, a side hike on the Grand Canyon. Pam LeBlanc photo

The next days were filled with loading and unloading boats, charging through waves the size of Volkswagen Beetles and exploring. One day, I climbed into an inflatable kayak with another paddler, and together, we ran a swirling Class 6 rapid, soaking ourselves to the core.

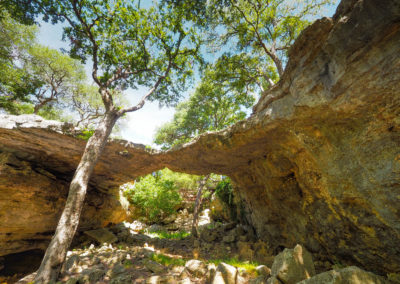

We hiked up slot canyons, through streams and into magical, fern-lined pools of shimmering water. We even made a “butt dam” in one narrow rivulet –– lining up bottom to bottom to back up the flow for a few minutes, then standing up and admiring the mini flash flood we’d created.

RELATED: Paddling, Hiking and Biking, oh my

At one hidden spot, we saw (but left in place) an earthenware pot 2 feet tall, stashed under the lip of a rock ledge. Humans have lived here at least 12,000 years; visitors should leave artifacts where they find them.

We had it easy, I thought, traveling with our guidebooks, high-tech equipment, mobile kitchen and coolers filled with food. What did those original inhabitants experience, scratching out an existence in this harsh setting?

Leslie Reuter and Mark Poindexter mud wrestle after an intense storm while rafting the Grand Canyon. Pam LeBlanc photo

The parade of adventures continued. A squall rose one afternoon and we tied off behind huge boulders to seek shelter. Afterward, an impromptu mud wrestling match broke out.

We spotted a few bighorn sheep on the cliff walls, a ringtail cat broke into the hatch of our boat one night, and a snake slithered through camp. In the evening, we played dominoes, read, and tossed horseshoes. Jimmy, Steffen and I topped off every night by sipping bourbon, discussing the day’s activities, and watching shooting stars blaze across the sliver of sky between the impossibly tall canyon walls.

Leslie Reuter prepares potatoes and burgers for dinner during a rafting trip on the Grand Canyon in fall 2021. Pam LeBlanc photo

Everyone gets a job

We divvied up chores. Two volunteered to cook dinner every day. We ate curries and burgers, quesadillas and stir fry, never once repeating a meal. Twice we enjoyed birthday cake made in a Dutch oven.

Others got up early to brew coffee and prepare breakfast. I was assigned dinner dish washing duty, scraping plates and straining dishwater by the light of a headlamp to prevent even a scrap of food from falling onto the beach or into the river.

One lucky person handled the “groover,” the metal can with an attached toilet seat. (The name comes from the grooves users acquired on their butt cheeks from squatting on ammo cans, in the days before toilet seats were used.) He set it up in one spectacular location after another.

If you’ve never pooped while gazing at a frothy rapid, put it on your must-do list.

Rafting the Grand Canyon by the numbers

About 5 million people visit Grand Canyon National Park yearly (closer to 3 million in 2020, due to pandemic limits), according to the 2021 edition of the “Guide to the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon.” Only about 25,000, or one half of 1 percent, see it from the bottom up. Most of those do it as a commercial trip, with guides to row them through.

Our group did what is called a “painless private” trip, paying an outfitter to provide rafts, a kitchen, a bathroom set-up, create a menu, and pack all of our food. We supplied our manpower and camping gear, did our own rigging, loading and unloading, camp setup, cooking, cleaning, and, of course, rowing.

The river’s flow was low, despite an active monsoon season. In 2020, less than 3 inches of rain fell in the canyon –– about a third of the usual amount. The water during our trip –– greenish-blue early on, then brown as hot chocolate after showers upstream flushed sediment into the water –– moved at about 9,000 cubic feet per second (cfs).

Pam LeBlanc looks over the Colorado River from a perch above Bass Camp while rafting through the Grand Canyon. Mollie Binion photo

The river drops an average of 7 feet per mile as it snakes through the Grand Canyon from Glen Canyon Dam to Lake Mead, cutting through a landscape that dates from 1,840 to 270 million years old. It’s like seeing time pass as you float through the river, watching cake-like layers appear and disappear from the walls that embrace you.

Unlike elsewhere, where rapids are rated on a 1 to 6 scale, rapids here are rated on a scale of 1 to 10. The water is powerful, but not as technical as other rivers. You won’t find many strainers, branches that can entrap a boater, because few trees grow along the river. You will find very powerful and swirly currents. Flush drowning is a danger, but more injuries occur in camp, where people twist ankles or fall in the water while making a night trip to pee in the river. (I used a can to save the treacherous trip.)

Luckily, our group included Mark Poindexter, an experienced paddler who has rafted and kayaked the Grand Canyon 21 times. He helped us scout proper lines through rapids and regaled us with stories. The most important thing to remember, he told us repeatedly, is to line up correctly and hit the waves straight on. Get sideways and you might flip.

All that worked, for the most part. But while I fretted over the big rapids like Crystal and Lava, we got nabbed by an innocuous one called Blacktail Rapid, a mere Class 3. We went sideways over a pour-over at the top, and the next thing I knew Jimmy was in the water, getting carried rapidly away from the raft while I hung over the edge like a pocket watch dangling from a pair of pants. Somehow, I managed to hoist myself back in, and Mark retrieved Jimmy.

Charlie Riou oars a boat through Lava Rapid. His passengers are buried in the wave up front. Pam LeBlanc photo

worried for an entire week about Lava Falls at Mile 179. Tim Cahill, a well-known adventure writer and co-founder of Outside Magazine, nearly died there after getting ejected from a raft in 2014. (He wrote this account of his near-death experience.) We’re acquaintances, and when I contacted him before my trip, he advised me not to try to fight the current if I did fall in. That’s a fruitless exercise, even for good swimmers.

In the end, every boat in our flotilla, including the one Jimmy rowed, made it through Lava unscathed. I wimped out, scrambling up and over a sketchy boulder field and snapping photos instead of riding through. I’m still comfortable with that decision.

It turns out I should have been more worried about Killer Fang Falls at Mile 232, where newlyweds Glen and Bessie Hyde presumably drowned on their honeymoon trip through the canyon in 1928. There we nearly pinned our raft on a voracious pair of ragged boulders. With Steffen at the helm, Jimmy and I threw ourselves to the high side of the raft, managing to slide her off at the critical moment. I think I peed my pants.

I took the oars for a few short stretches but struggled to make the raft go where I wanted it to go. Rafts are strange. You can go forward or backward, which gets confusing, and I didn’t spend enough time to commit the motion to muscle memory. I did navigate one tiny riffle, much to the amusement of my passengers, with some coaching from the veterans.

A rafting trip a long time coming

We got used to seeing Marcy Beard, John’s wife, with a clipboard and pen in hand each evening, plotting what ingredients we’d need for the next meals or checking the weather forecast. She worked hard behind the scenes but avoided the spotlight.

One evening, though, as we pulled our camp chairs into a circle for the nightly meeting and stories, she spoke up.

“Twenty-five years ago, John put in for a permit,” she told the group. Through marriage, she had inherited that spot on the waiting list. Tonight was their anniversary. She turned to those gathered around her –– every one of us, I think, beaming beneath the moonlight and flush with the contentment that comes with spending days on end outdoors. “I’m happy to be here and to share it with you.”

To say I’m grateful I got invited is an understatement. A few days later, as the end of the 260-mile trip neared, I ask John if the experience had matched his expectations.

The water turned from blue-green to muddy brown about two-thirds of the way through the 260-mile trip. Pam LeBlanc photo

“Yeah,” he said, pausing long enough that I noticed his eyes sparkle and a smile form. “Even better.”

A trip like this will reset your life. It shifted me into what felt like a more natural mode than modern life, with all its fancy conveniences and entrapments. Without social media to update or assignments to file or flights to catch or appointments to make, I could sit with my thoughts and just think.

Unlike that water, which turned from blue-green to muddy brown, the message became clearer as we ticked off the miles. Humans were meant to move at the pace of a molasses-colored river.

The Colorado River rounds a bend at Bass Camp, one of the places we stopped for the night during a three-week rafting trip on the Grand Canyon. Pam LeBlanc photo

If You Go

Getting there:

Book a non-stop flight from Austin to Phoenix, then rent a car for the drive to Flagstaff. Grand Canyon Private Boaters Association has a list of companies that can outfit your trip and provide shuttle service. We used PRO, Professional River Outfitters.

Stay:

Pack a tent or roll out a sleeping bag under the stars. For more information about the National Park Service’s lottery system to secure a permit, go here. Remember, it can take years to get one.

Do:

Twenty-one days of rafting, hiking, swimming and exploring. It won’t be enough.

Eat & Drink

Hire an outfitter like PRO to provision the trip. They can help with menus and accommodate dietary restrictions.

Pro tip:

Bring a game or too, like dominoes. Some of our best times in camp came were gathered around a crate for a game of 42.