A Northern fence lizard shows off its blue belly at the Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary in East Texas. Pam LeBlanc photo

It doesn’t take long — less than a minute, in fact — before the first cool discovery at Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary: A fence lizard doing “push-ups” atop a wooden post.

The pretty little lizard is warning other males in the area not to mess with him as he pumps up and down, flashing his bright blue belly, according to sanctuary manager Shawn Benedict. He picks up the reptile so I can get a closer look. After admiring it for a few minutes, he releases the animal and we head down a trail at the sanctuary, located 25 miles north of Beaumont.

This land once belonged to the Temple family, whose history in forest operations in East Texas dates back more than a century. In 1977, Time Inc. and Temple-Eastex Inc. donated 2,138 acres to the Nature Conservancy of Texas to create the sanctuary, with the goal of protecting and sustaining native species. Over the years, several smaller tracts were added. In 1994, Temple-Inland donated more acreage, doubling its size with a conservation easement that limits development. The whole project, including the preserve and adjoining easement, now covers nearly 6,000 acres.

RELATED: Discover the diversity of LBJ National Grasslands

It’s one of two Nature Conservancy properties in Texas — the other is Lennox Woods in northeast Texas — that is open to the public 365 days a year. People can come here to hike, watch birds, trail run, and paddle. It’s open daily from sunrise to sunset.

Go for an East Texas hike

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

I tromp down a trail behind Benedict, who is a wildlife biologist and has lived on site since 2008. We pass a covered pavilion with picnic tables and some big post oak trees dripping with Spanish moss, and almost instantly the forest swallows us whole.

More than 6 miles of marked pathways weave through the property, dipping from the sandy uplands filled with tall swaying pines to sloping forests dotted with magnolia trees. Things look entirely different down along Village Creek, a tributary of the Neches River that cuts through the sanctuary in a tea-colored ribbon and is open to paddlers.

RELATED: Women, Wind and Waves: Surfing for Adventure

This land teems with life, from deer, coyote and bobcat to hundreds of types of plants. In all, more than 700 species grow here, including prickly pear cactus and yuccas, pines and four globally endangered plants including the Texas trailing phlox. The preserve lands are part of the upper loop of the Coastal Birding Trail, too, and are home to the Bachman’s sparrow, a state threatened species, and the brown-headed nuthatch.

A bright red coralbean plant grows at the Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary in East Texas. Pam LeBlanc photo

We pass coralbean plants, with their tall stalks of tubular red flowers, and stands of loblolly pines. A zebra swallowtail butterfly flits past, a bronze frog croaks in the distance, and when we step off trail, a snake skitters out of our way.

Visitors can pick up a pamphlet that explains things you’ll see along the trail. “It’s like having a biologist with you, just in a book,” Benedict says.

Longleaf pine, the star of Sandyland Sanctuary

Loblolly and longleaf pines grow at the Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary in East Texas. Pam LeBlanc photo

But the longleaf pine is the star. Historically, the tree covered 90 million acres between East Texas and Florida. The area was heavily logged at the turn of the century, though, and today it covers just 6 million acres. The Nature Conservancy is working with other agencies to expand that area.

“This is what East Texas is supposed to look like — not a whole lot of brush, not a whole lot of trees,” Benedict tells me when we get to an area where the longleaf pine are scattered across the landscape. “You should be able to see through it.”

He points out the clumps of needles that sprout from the end of slander branches. The needles are as long as spaghetti strands.

“They look like Cousin Itt from ‘The Addams Family,’” Benedict says.

They also need good forest management. Preserve managers ignite sections every 18 months or so to select for longleaf pine, which can survive a prescribed burn. Other non-native species die off in the periodic blazes.

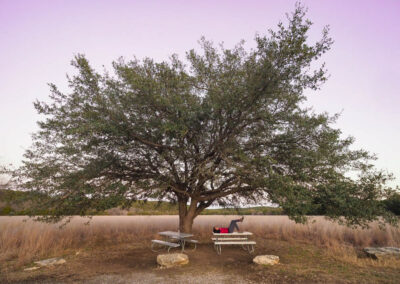

Shawn Benedict, manager of the Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary, hikes into the forest. Pam LeBlanc photo

After a couple of hours of exploring, we head back out. I’ve seen some cool critters and gotten a taste of what this part of the Lone Star State once looked like.

Most importantly, I’ve gained a new appreciation for longleaf pine, which can live up to 400 years.